A couple of months ago Clara Rockmore was featured as the Google Doodle and it got me thinking about this book and how easy it is to get so swept up in historical fiction that you either A) forget that it's fiction, or B) forget that the characters in the fictional account were actually real, or perhaps some combination of A and B resulting in completely losing your grip on reality and slipping through the looking glass. Hasn't that happened to you? Anyway, historical fiction can be powerful stuff, approach with caution.

Winner of the 2014 Scotiabank Giller Prize, Us Conductors is the captivating fictional account of real Russian scientist, spy, and inventor of the theremin, Lev Termen (Leon Theremin) and his muse, electronic music pioneer Clara Rockmore. The story, told through correspondence and flashbacks, speculates about Termen's unrequieted love for Rockmore, and the circumstances surrounding his return to the Soviet Union. Once I finished this beautiful book I couldn't let the story go, so I immersed myself in YouTube videos and audio recordings of Lev and Clara playing the theremin. Clara Rockmore was a classical violin prodigy from Lithuania. Suffering from tendonitis she was forced to give up her beloved instrument, but was later introduced by Termen to his invention: an electronic musical instrument controlled by gesture. She helped refine the instrument, and defined it as an art form, becoming its most prominent performer. I've included a couple of the videos to pique your curiosity.

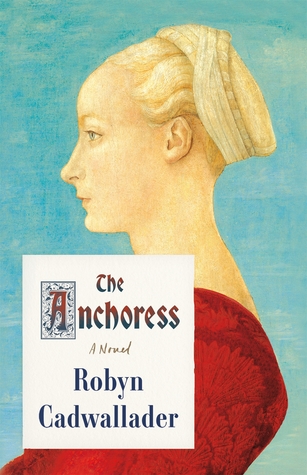

by Robyn Cadwallader

The Anchoress is the fictional account of a (probably fictional) anchoress in 1255 named Sarah. What's an anchoress? Good question! Until a patron recommended this book to me, I admit that I didn't have a clue. Then I did some googling. In Medieval Europe, an anchorite was a religious recluse, someone who would lock themselves away, denying themselves all but the very minimum required for survival. They felt that through complete solitude and denial of all earthly pleasures they were "hanging on the cross with Christ". They would be enclosed for the rest of their lives in a tiny cell adjoined to a church and were a symbol of piety and a source of comfort for their communities, living out their days in contemplative prayer. Author Robyn Cadwallader takes the reader into Sarah's time and culture, her tiny cell, and delves deep into her mind and motivations.

| An anchorites' cell in England |

Looking for more? Check out Thomas Mallon's recent, well-reviewed Finale: A Novel of The Reagan Years, or The Revenant by Michael Punke (I could go on all day). You'll enjoy exploring the real people or events behind these marvelous fictional tales as much as the tales themselves.