This image appeared at the top of the Richmond Planet, the country’s longest-running weekly black newspaper, beginning in 1895. Its artist, John Mitchell, Jr., was the paper’s editor and first editorial cartoonist, as well as being, over the course of a life that began in slavery in 1863, a teacher, an alderman, an activist, and a bank president.

Writing about Mitchell’s reputation in the years after his death in 1929, his biographer, Ann Field Alexander, noted, “His story was too complex to lend itself well to presentations during Negro History Week, and even his most solid achievements—his editing of the Planet, his crusade against lynching, his work on the city council, his fight for black officers during the Spanish-American War, his leadership of the streetcar boycott—did not fit in well with a celebratory view of Virginia’s past.”

Now 87 years after his death and 21 years after the newspaper he devoted his life to ceased publication in Black History Month, 1996, Mitchell’s achievements occupy a much firmer place in the celebration of Virginia’s past, thanks in part to Alexander’s biography, Race Man: the Rise and Fall of the “Fighting Editor” John Mitchell Jr., and efforts to digitize and preserve copies of the Richmond Planet at the Library of Virginia and the Library of Congress.

Issues from 1889 to 1922 are online, and what can’t be seen online may be available in microfilm at the Main branch downtown. Reading the Planet in any format is an excellent way to learn about black businesses in Richmond, the history of the black community and the police, even the art of editorial cartooning.

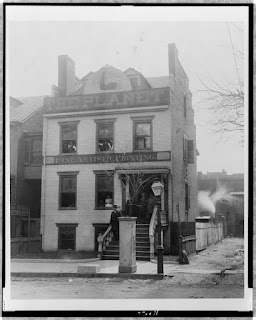

A few scrolls through the microfilm or the website, for instance, reveal Mitchell’s clenched-fist symbol used in advertisements as early as four years before it appeared on the cover. The flexed arm amid bolts of lightning retakes strength and power from the oppressors of black Americans, the same way the "We Can Do It!" poster came to retake strength and power from the oppressors of women. When Mitchell moved the Planet out of the Swan Tavern on East Broad in 1897, his new offices bore a large sign presenting the Planet’s arm and fist to Jackson Ward.

Beneath the paper’s logo, the Planet regularly included Mitchell’s simple but effective cartoons, the first known cartoons published in a black, Southern paper. In 1918, however, Mitchell stepped down as editorial cartoonist and hired George H. Ben Johnson in his place. Despite Johnson’s talent and the fierceness of his approach, he remains a mysterious figure in Richmond history and the history of black art. In their exhibit on the Richmond Planet the Library of Virginia noted that “almost nothing is known about Johnson aside from his name and the legacy of his cartoons.”

Born in Richmond in 1888, Mitchell studied at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, the Landon School of Illustration and Cartooning, and Columbia University. In 1917 Mitchell published a small book of Johnson’s work, Souvenir Cartoons. The typically one-panel cartoons featured realistically rendered black men and women against starkly blank backgrounds, as well as African imagery—the pyramids and the Sphinx—used to remind the Planet’s readers that black history is ancient. In a cartoon titled "American Ideals," the Statue of Liberty holds a sign reading, "Liberty, protection, opportunity, happiness for all white men. Humiliation, segregation, lynching, etc. for all black men. All are welcome."

After working at the Planet Johnson continued to draw and paint. In 1926 he wrote a letter to W.E.B. Du Bois while in New York asking if Du Bois would like to view his cartoons for possible publication in Du Bois’s magazine The Crisis. The next year he exhibited at the Richmond Public Library, and in 1945, he won a prize from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. His painting Idyll of Virginia Mountains remains in the VMFA’s collection.

For now, Johnson's name appears in only a few encyclopedias and collections. As Mitchell makes his way further into our view of Virginia’s past, hopefully Johnson will follow and more of his life and work will be known and shared.

No comments:

Post a Comment